Many years after fleeing into exile, Sazan M Mandalawi returns to her homeland to help youth whose lives are on hold.

I was born a refugee in Iranian Kurdistan. A year before my birth, Saddam Hussein launched a campaign of genocide against the Kurdish people; thousands in the Kurdish city of Halabja, Iraq were killed by a chemical weapons attack.

Later, when I was five, we attempted to flee Iraqi Kurdistan, living as refugees before returning home a year later. A second attempt to flee into exile succeeded a few years later. Thus, before my eighth birthday, I arrived as an immigrant, continents away from my parent’s homeland, in Australia.

After many years of living “down under”, my parents decided to return to our homeland of Iraqi Kurdistan. I was 16. The announcement had me crying under my blanket at night on more than one occasion. My “good life” was coming to an end – or so I thought.

If you had told me back then that one day I would be standing in a tiny caravan, amidst a sea of tent roofs in the middle of what looks like a muddy desert, I would never have believed you. My time here, however, is being spent rather differently than my past periods as a refugee.

The Kurds

The majority of Kurds are Sunni Muslim, though in Iraqi Kurdistan it is not unusual to see a mosque, church and Yezidi shrine in a single glance. Kurds share a unique language, culture, and tradition within the Middle East. Today, the larger Kurdistan (Land of Kurds) is divided between Iraq, Turkey, Iran and Syria. The worldwide population of Kurds is estimated to be roughly 30 million, making Kurdistan the world’s largest stateless nation. They have suffered decades of repression with a history of genocide in Iraq and Turkey. Today, Kurds in Iraq have gained significant autonomy, but are yet to claim total independence.

The Domiz camp, where I am based as I write this piece, is like a town of its own. The residents here are more than 40,000 Kurds who have fled the massacre in Syria. Parents have left behind destroyed houses and their life savings to live across the border in a tent with their five children. Families want to remain alive, to be protected.

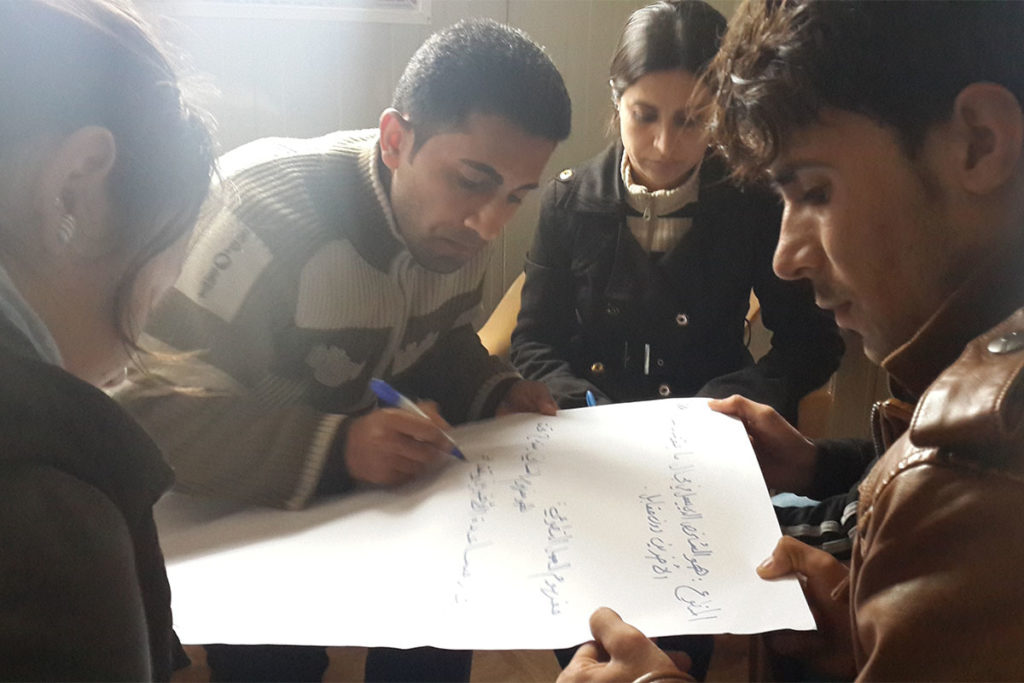

Not long ago we were at a different camp. For five days we trained 22 people on life skills to adopt in their daily routine. To the patter of rain, we conducted the training as the wind swayed the large tent walls from right to left. The temperature was too cold for our hands to hold a marker. It was the physical movement of icebreaking activities every half-hour that kept us going.

“Shall we cancel for today?” we asked on many occasions. The unanimous reply from the participants was always, “No way!”

In the summer months, power cuts struck the caravan amid 50-degree desert heat. I felt as though all the water in my body had evaporated. Still, no one wanted to cancel any of the peer education sessions.

Back when I first returned to Kurdistan I volunteered with a local NGO, START. There I was introduced to an initiative of the United Nations Population Fund called Youth Peer Education, or Y-Peer. Through interactive, fun methods we train youth on life skills, as well as issues and taboos faced by youth in these environments, including early marriages, HIV/AIDS, sexual and reproductive health, anger and depression management, family relations and female genital mutilation. Each person we train becomes a peer educator as well, and he or she goes on to conduct another session of about 20 youth. You can imagine the impact of this multiplier effect across the camp.

When a depressed, frustrated youth leaves a note reading, “You changed my life… you gave me hope,” I feel as content as a butterfly basking in a sunny rose garden.

If they can live with such modest needs, why must we live with so many wants?

Every time we hold the training for a group of youth in the camp, the three-hour drive back to my city, Erbil, feels a decade away. A house, car and fancy furniture are trivial things, I think to myself. Sitting in the back seat, looking out the window at the beautiful nature of my homeland, I am struck by what feels like an epidemic of guilt gnawing away at me. If they can live with such modest needs, why must we live with so many wants?

How many times have we heard these first world problems?

(whining) “I want the new iPhone!”

“Their fettuccine alfredo was awful!”

(staring into a jam-packed wardrobe) “I haven’t got any clothes to wear!”

(demanding) “I want an Elie Saab dress made for me!”

Or the birthday wish to be gifted that coveted Louis Vuitton handbag.

Spending a week at a refugee camp teaches you that there’s more to life. My priorities have changed. On every trip to the camps, I conclude that I belong here.

At times my heart wants to shed tears of blood. Here, girls get married at very young ages, often to remove the weight from their families. Talented youth leave their studies in medicine, engineering, arts, accounting, science and other subjects. They put their lives and ambitions on hold simply to be safe with their families. Some are not allowed to leave their tents when they wish; others are bored; some want to go to a nearby city but cannot afford the expense. And the sheer uncertainty means that no one knows how long they’ll have to endure life in the camp. After a year, how many more are left? Nobody knows. It may end up being one, two, three, four or more years before they can again press the play button to get on with their lives.

Sometimes I feel as though I want to wave a wand and heal the pains of all the youth we train. Yesterday I cried, and so did two of my colleagues, as one of our participants shared her story with us. It is true that you never fully realize your privileges until you see the pain of others.

To date, we have trained around 120 youth in three refugee camps in the Kurdistan region. That’s 120 lives changed; 120 youth who are more informed; 120 new friends. They have taught me more about life than any tweet, Facebook status or video-share from YouTube.

At the time, returning to a developing country seemed to me like the worst decision my parents could make for their teenage daughter who was trying to find her place in the world. Today, I can say that I wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Each time I get a call or text from one of my 120 friends, I know exactly why my return to my homeland allowed me to find my place in this world.

As I pack my things after each training, I know there is more in my bag than a few changes of clothes and a towel. Along with physical items, I also pack important lessons: family and good health is the top priority; a roof above your head is cause for thanks; and be thankful for the little things in life. Finally, I’ve learned to pack my tasbih (prayer beads) to repeatedly say Alhamdulillah for all I have.

All photos courtesy of Sazan M Mandalawi unless otherwise stated