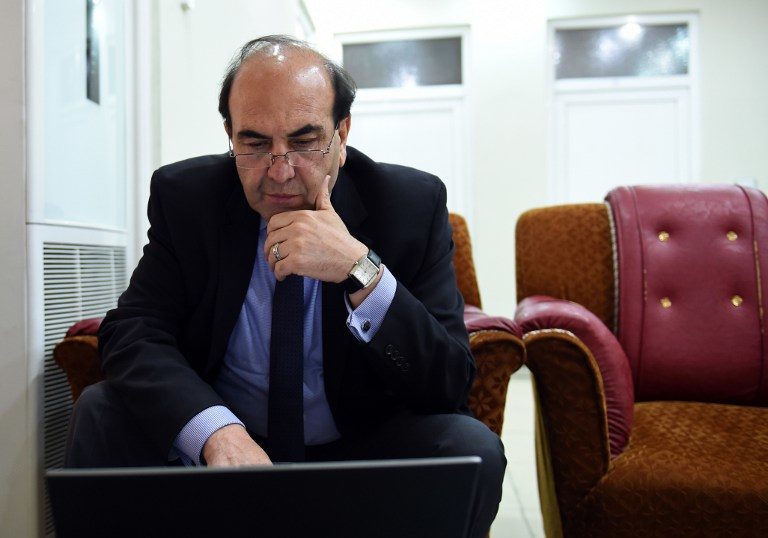

In this photograph taken on April 5, 2015, Hamidullah Farooqi, an economist appointed by Afghan president Ashraf Ghani to lead an anti-corruption inquiry into fuel contracts, works on his laptop at his office in Kabul. Ringed with snipers and sandbag bunkers, the fortified makeshift office of a Kabul academic spearheading President Ashraf Ghani’s unprecedented anti-corruption drive could be mistaken for a military garrison.

By Anuj CHOPRA

Ringed with snipers and sandbag bunkers, the makeshift office of a Kabul academic spearheading President Ashraf Ghani’s unprecedented anti-corruption drive could be mistaken for a military garrison.

“I used to live an ordinary life driving an ordinary Toyota,” Hamidullah Farooqi, 62, told AFP, reading glasses perched on his forehead.

“But investigating corruption means investigating people with dangerous connections. It’s like fighting the mafia — the economic mafia.”

Corruption in Afghanistan is not just another issue. It is arguably the single biggest challenge confronting the troubled country as it rebuilds itself after decades of war.

It permeates nearly every public institution, hobbling development despite hundreds of billions of dollars of foreign aid over the past decade, sapping already bare state coffers and fuelling insecurity as alienated Afghans veer towards the Taliban.

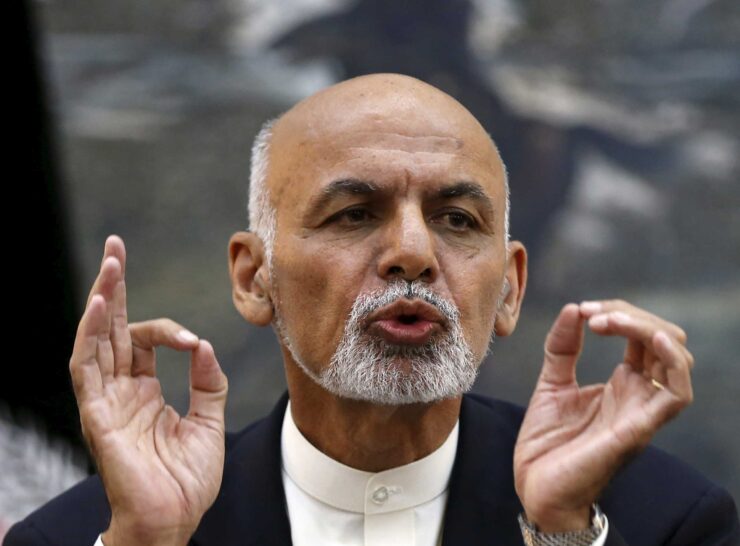

Since coming to power in September, Ghani, an American-educated former World Bank official, appears to be cracking down hard.

He launched a probe into 12 military logistics contracts, reopened the investigation into a major banking scandal and sacked nearly the entire administration of western Herat province accused of corruption or incompetence.

Handpicked by Ghani to oversee his anti-graft campaign is Farooqi, a Kabul University economics lecturer who was part of the president’s election campaign last year.

The most high-profile among these cases are contracts to supply fuel to the Afghan military worth nearly $1 billion, approved by the previous Hamid Karzai-led government.

In this photograph taken on April 5, 2015, Hamidullah Farooqi (R), an economist appointed by Afghan president Ashraf Ghani to lead an anti-corruption inquiry into fuel contracts, speaks with visitors at his office in Kabul. Ringed with snipers and sandbag bunkers, the fortified makeshift office of a Kabul academic spearheading President Ashraf Ghani’s unprecedented anti-corruption drive could be mistaken for a military garrison.

‘Dirty tricks’

Farooqi said the contracts, which Ghani terminated, involved “sophisticated” white-collar fraud.

“When you take a look at the paperwork, everything looks perfectly normal and by the book, but closer scrutiny reveals the anomalies, the fraud,” he said.

Last week, Farooqi discovered one eye-popping detail that helped uncover the graft: four companies vying for the contracts submitted the exact same bidding prices — the numbers matched right up to the last decimal place.

“That’s only possible… if there is bidder collusion or if the price list is leaked (from inside the government),” he said.

One company, Afghan National Petroleum (ANP), alleged that on the day of the bidding, traffic police — in cahoots with its competitors — deliberately waylaid its vehicle to keep them out of the competition.

“The cops found fault with our license plate, blocking our vehicle with one police car in the front and another behind. We eventually arrived 20 minutes late and were told we couldn’t bid,” ANP chief Mahmoud Qaderi told AFP.

“It was a dirty trick,” he said, a complaint believed by Farooqi, who has submitted his findings to Ghani.

The probe — the first of its kind — is a test case for Afghanistan and has forced the government to reassess how official contracts are awarded, a process long prone to bribery and influence-peddling, said a senior Ghani administration official advising Farooqi’s team.

“We are re-examining several past contracts, scrutinizing them page by page, line by line, to check if they are deliberately designed to favor somebody,” the official told AFP, requesting anonymity.

That has resulted in a huge backlog and the advisor admitted to fielding calls from political strongmen and former warlords with vested business interests who are “uncomfortable” with the scrutiny.

“I am understanding instructions from the president to tell them to ‘buzz off’,” he said.

To watch his back, he said he had installed an automatic call recording app on his phone to tape incoming calls.

“It will take time for the message to filter down that it’s no longer ‘business as usual’,” he said.

‘Integrated criminal networks’

Ghani has projected himself as the very antithesis of his predecessor Karzai, who critics say paid only lip service to eliminate corruption during his 13 years in office.

Ghani has developed something of a reputation for his surprise swoops on public institutions at odd hours, routinely dressing down and sacking those found to be inept or corrupt.

But he has struggled to find replacements at the same rate, with most of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces led by acting officials and several cabinet positions remaining vacant.

Critics say Ghani is hamstrung by political compulsions and is unwilling — or unable — to go after many of the powerful elite implicated in corruption scandals.

“It’s all very well to reopen the Kabul Bank case, but has he put any of the masterminds in jail? Has he recovered the lost money? No,” said anti-corruption activist Seema Ghani, alluding to a $900 million fraud that wrecked the country’s largest bank.

Ghani’s drive also understates the scale of the problem, said Sarah Chayes, author of “Thieves of State: Why Corruption Threatens Global Security”, which cites interviews and other research showing graft-weary Afghans are becoming more susceptible to Taliban propaganda.

“Ghani does not preside over a government that is plagued by a ‘cancer’ of corruption,” Chayes told AFP.

“He presides over something that has crystallized over the past decade into… a set of sophisticated, vertically integrated criminal networks.”

Still, for the first time in years, the country has a leader who is taking a stand against corruption — and that in itself marks a sea change for Afghanistan, the administration official said.

“He (Ghani) knows it will take years if not decades to clean the system,” he said.